Research on Wandering

Wandering is a symptom commonly attributed to dementia. Research hasn't produced a clear definition of wandering and the prevalence of wandering within those who have cognitive impairment ranges widely. Wandering itself isn't necessarily a concern. In fact, there are benefits to wandering such as promotion of circulation and oxygenation, improved mental health outcomes, exercise, etc. That said, unsafe wandering can lead to injury to oneself or others, or even death.Therefore, providing high-quality, person-centred care for those with dementia should be informed by a rich understanding of interventions and best practice recommendations for senior care residencies and nursing homes related to falls, wandering and elopement.

To date, research has concluded that there is no strong evidence pointing to any intervention as being particularly effective when it comes to preventing wandering. Exposure to multi-sensory environments and the implementation of an early-evening walking program showed small, statistically significant reductions in aggression and restlessness. That said, a review of the literature around restraints indicates that restraints do not prevent wandering or falls. Additionally, there is no evidence to suggest they're useful in residential, assisted living or nursing home settings.

Understanding The Impulse to Wander

In order to prevent unsafe wandering, it can be helpful to understand why an individual has developed a habit of wandering. There are a wide variety of reasons why someone might wander, including:

- Anxiety or fear: The individual may wander as a reaction to feeling nervous or unfamiliar with their environment.

- Searching: The person may get lost while searching for a person, place or object.

- Routine: He or she may have had a routine of walking at certain times of day (i.e. to work, to pick up children from school, etc.). It helps to find out their past daily rhythms to gather ideas of how best to reassure and redirect them.

- Physical discomfort: They may be hungry, in pain, needing to use the restroom, or bothered by light, noise, temperature or smell.

- Boredom: If there is no one to interact with and nothing to do, someone may wander out of sheer boredom.

Care staff or family caregivers should observe carefully and be attentive to the wandering in order to decipher what the individual is trying to express or communicate.

Preventing Unsafe Wandering

Provide safe zones

Many care providers are creating safe places for wanderers to wander. Whether it's an entire gated community or a large garden, there are many creative ways to validate one's need to explore.

Ensure basic needs are met

Regularly check that an individual's most basic needs are met. Are they too hot or cold? Do they need to use the toilet? Do they need food or drink? Are they in any pain? Do they need an activity to do or reassurance about their safety?

Identify patterns

Identify times of day that wandering tends to occur and then plan activities to keep that individual focused and engaged in something.

Validate and redirect

Avoid correcting someone with dementia if they're not making any logical sense. Instead, consider ways to validate what they are feeling and redirect their attention.

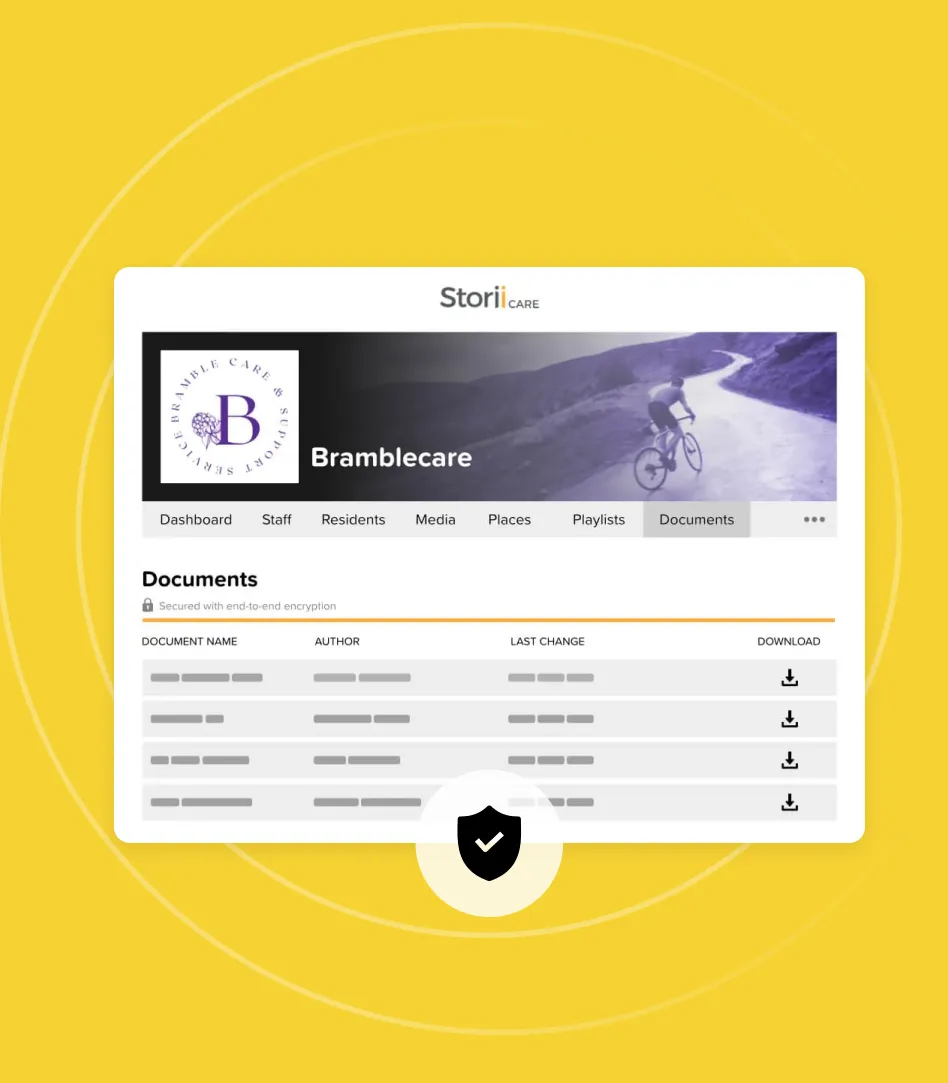

Install safety equipment

Adequate, continuous supervision is ideal. However, staff and family caregivers can't always be by someone's side 24/7. The health tech market is full of falls-prevention and safety gadgets. As alternatives to restraints, consider placing pressure-sensitive alarm mats at bedsides, using childproof covers on doorknobs or sliding bolt locks out of their line of vision. There is a wide variety of devices that can be tailored to an individual and alert you that they are on the move.

Remove 'leaving' items

Keep things like shoes, coats, hats, keys, etc. out of sight. These items are associated with leaving home and can become triggers for elopement.

Camouflage doors

Paint doors the same color as the walls surrounding them. Alternatively, place removable curtains over doors.

.png)

.png)